The idea of carbon emissions trading began in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro. At that time, around 160 countries agreed to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Carbon markets are carbon pricing mechanisms that enable governments and non-state actors to trade greenhouse gas emission credits. Their aim is to achieve climate targets and reduce the negative externalities caused by carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, the number of carbon markets is increasing, with many developed countries, including the EU, now having a mechanism to trade the quantity of carbon emissions that a company can produce.

There are several benefits to trading carbon emissions, such as reducing the cost of cutting emissions, making the carbon price more stable, rewarding low-emission practices among businesses, leveling the international playing field by harmonizing carbon prices across jurisdictions, and supporting global cooperation on climate change. On the other hand, one of the main problems arising from carbon emissions trading is the possibility for firms to engage in carbon leakage. Carbon leakage occurs when, for economic reasons related to climate policies, businesses transfer polluting activities to other countries where there is less regulation. This can lead to an overall increase in emissions. Estimates of leakage rates vary between 5% and 20% as a result of the loss in price competitiveness that firms experience when complying with stricter climate regulations.

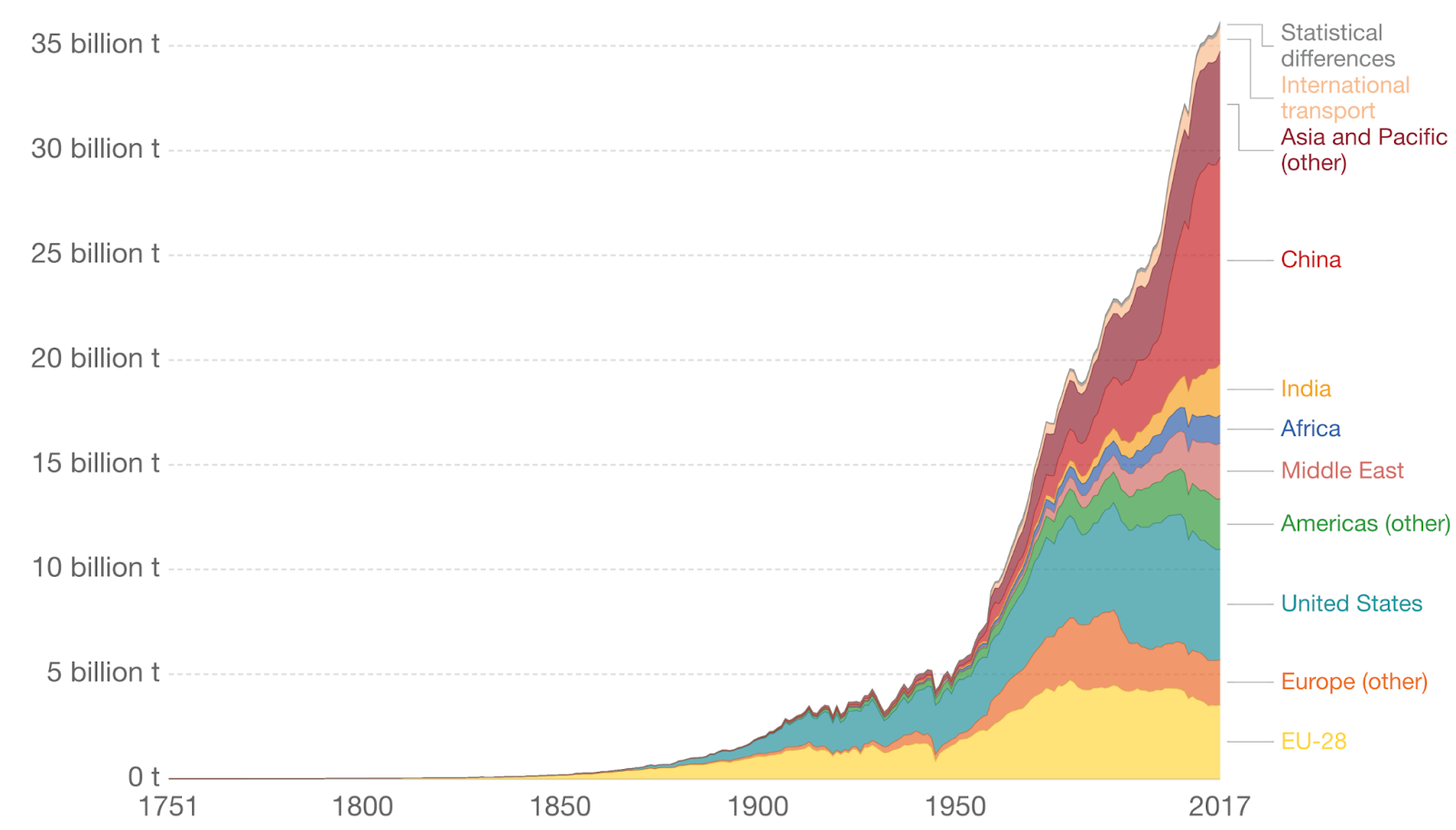

For example, for years, carbon emissions in the U.S. and Europe have been decreasing. However, in developing countries such as China and India, emissions are rapidly increasing. While the rise in greenhouse gas emissions in developing countries is mostly due to domestic growth, there is also a component derived from companies in more economically developed countries that set up factories abroad to cut costs and avoid regulations, thus further contributing to global pollution.

There are many challenges to the proper functioning of this system. One of the main ones is that many companies self-report their emissions, which can lead to manipulation or unintentional inaccuracies. Moreover, there is significant variability in measuring and reporting standards across various jurisdictions. Many multinational companies also have global value chains, making it harder to calculate their emissions and increasing the probability of non-compliant suppliers. Moreover, even if non-compliance is detected, the complexity of emissions accounting makes it very difficult to prove. In addition to all of this, the bureaucratic complexity of this international effort to reduce emissions means that issuing fines or imposing other sanctions is a lengthy process.

Source: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC); Global Carbon Project (GCP)

Note: The difference between the global estimate and the sum of national totals is labeled “Statistical differences”.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

To try and solve the problem of carbon leaking the EU has decided to implement a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, more commonly known as CBAM. This tool aims at fairly pricing carbon emissions released into the atmosphere as a consequence of the production of carbon intensive goods entering the European market, with the goal of promoting more sustainable production in non EU countries. CBAM aims to solve the aforementioned problem of carbon leaking, ensuring that products made inside the EU respecting environmental concerns aren’t hurt by unfair competition of products made disregarding their environmental impact. This is achieved by making sure that the carbon price of imports is equivalent to that of domestic production, while adhering to WTO rules.

This program will come in full effect from 2026 with a transitional phase from 2023 to 2025. During the initial transitional phase importers of certain goods whose production is carbon intensive (cement, iron, aluminum, steel, etc…) will only have to report the embedded carbon emissions of their products but won’t have to pay for their emissions. From 2026 onwards importers will have to purchase CBAM certificates, declare emission and give up a number of certificates based on the volume of emissions. However, if importers prove that a carbon price has already been paid for the production of the good, this amount can be discounted.

As previously mentioned, CBAM aims at pricing the emissions of goods imported to the EU to prevent firms from relocating to cut costs, which would decrease growth within the EU. This all sounds good in theory, but in practice there are still a few issues which need to be solved. One of the main challenges is data recollection. CBAM is based around the quantification of the cost of emissions, and the problem lies precisely there. To fulfil reporting obligations, importers in the EU require huge amounts of data from suppliers over whom they have little control. Even in face of this, importers can be held liable under CBAM regulations for misreporting emissions. Excessive regulations may disincentivize business activity in the EU. Another problem is the disproportionate impact it can have over developing countries. Although the countries most affected by CBAM in terms of volume are developed countries, when we take a look at the relative impact it is much greater for developing countries. This comes as a result of the increased level of dependence that developing countries have on exports to the EU. For example, one of the most affected countries by CBAM is Mozambique, as near 20% of its total exports, mainly composed of aluminum, fall under CBAM regulations.

In conclusion, we believe carbon markets are an ingenious idea to hold firms accountable for the emissions they create and encourage a transition to a more sustainable future. Even though these systems help to internalize the costs of emissions, there are still many challenges such as carbon leakage, which still need to be resolved. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is a prime example of how to address carbon leakage. Even though it still has some issues to solve, CBAM has the potential to become a key piece in the fight against climate change.

Written by Gian Paolo Cecchini and Mario Di Salvo

Sources

- https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en

- https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/05/a-political-economy-perspective-on-the-eus-carbon-border-tax?lang=en¢er=europe

- https://gmk.center/en/opinion/the-main-current-problem-of-cbam-implementation-is-uncertainty-and-unpredictability/#:~:text=Challenges%20in%20implementing%20CBAM,of%20uncertainty%20remains%20very%20high.

- https://clear.ucdavis.edu/news/what-carbon-leakage

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/free-allocation/carbon-leakage_en#:~:text=Carbon%20leakage%20refers%20to%20the,increase%20in%20their%20total%20emissions.

- https://www.unep.org/topics/climate-action/climate-finance/carbon-markets

- https://carbonmarketwatch.org/

- https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/international-carbon-market_en

- OurWorldInData.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions