In a world that, despite its great heralds of climate change and environmental degradation, often remains recalcitrant – that still balks at the necessary steps needed for effectual improvements, the Danish energy company Ørsted is the exception.

In the early 2000s, at the dawn of a new era of sustainable awareness and policy pressure, with the introduction of the first European legally binding targets for renewables and energy efficiency, Ørsted’s forerunner DONG Danish Oil and Natural Gas, with its 90% fossil-fuel based business core and emissions accounting for one third of Danish CO2, was bound to be greatly affected by the changing landscape.

When DONG slid into financial crisis in 2012 amid the European energy market instability, where others would have tried to weather the storm with layoff and cost shrinking, newly hired CEO Henrik Poulsen saw the opportunity for a paradigm shift: “It had to be a radical transformation; we needed to build a new core business and find new areas of sustainable growth. We looked at the shift to combat climate change, and we became one of the few companies to wholeheartedly make this profound decision, to be one of the first to go from black to green energy”.

Any transformation comes with its growing pains, though. When DONG first changed name to Ørsted and divested in its oil, gas and coal, it naturally saw its revenues dive, creating an earning gap that couldn’t be filled by the renewable sources the company had started phasing in, eminently offshore wind power, which at the time generated energy at double the price of onshore wind.

Offshore wind, at the time of Ørsted’s first investments in it, was still a very expensive and young technology, with no guarantee of commercial viability despite its capital-intensive nature. Government subsidies were still a rarity and relied on the cost reduction potential, which therefore Ørsted had to provide.

Under Poulsen’s leadership, Ørsted started on a seemingly insurmountable mission: a systematic “cost-out” initiative aimed at lowering the expense of offshore wind production while achieving greater economies of scale. Remarkably, it worked, with costs dropping by 60% and enough financial stability to guarantee expansions in the USA and in the UK. It started being traded on the Nasdaq Nordic.

Today Ørsted’s profits have increased by more than $3 billion since its revolution and is the largest offshore wind company in the world.

According to its executives, what made this sector so profitable for Ørsted was the approach they took: they set visionary objectives instead of incremental targets from the bottom up. This fostered a transformative approach that turned out to be pivotal for the whole sector. It encouraged larger sites, innovation, procurement optimization. They made possible the impossible: making the offshore wind competitive with coal and gas power plants and surpassing all the promises they had set for themselves – they had initially planned to reach 85% green sources by 2040, a target instead surpassed much faster, which is an incredible rarity in any company.

What can we learn from Ørsted’s transformation?

First and foremost, one needs to keep in mind that on average 70% of change efforts fail. Ørsted’s example stands out as one of the few successful core business transformations. One can better understand the key elements of their successful transformation thanks to the 8 Steps for Leading Change of John Kotter.

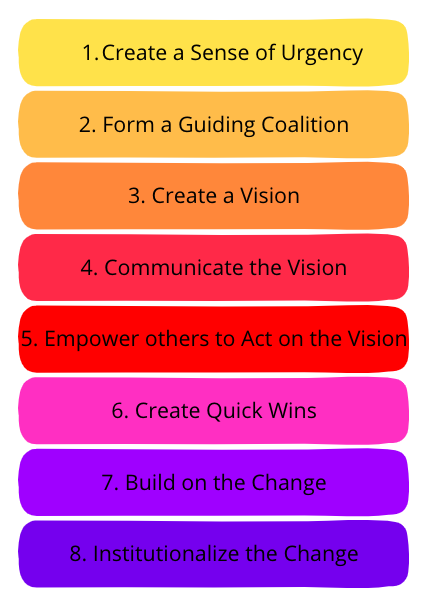

Adapted from Kotter’s 8 stages of change (Kotter, 2012)

These 8 stages of change are critical to achieve successful and long-lasting change according to Kotter. One could identify several of these steps in Ørsted’s change efforts. More importantly, 3 elements seemed to have set their transformation up for success early on:

Creation of a sense of urgency: executives acknowledged the evolution of the regulations and the climate change crisis. They used it to create a sense of urgency: the company needed to act immediately.

Formation of a guiding coalition: executives quickly realized that they could not scale up offshore wind projects alone. Their main concerns were regarding their supply chain and financing models.

Thus, they formed partnerships with suppliers such as Siemens for their turbines and bought an installation company called A2SEA. They also developed the farm-down model, in which half of their projects were funded by financial partners who relied on project financing. It enabled them to free up part of their own capital and to pursue many projects at the same time.

Development of their vision: they envisioned a future centered around clean energy for their company and enacted it with a strategy. Their strategy was to switch their portfolio mix from 85% of fossil fuels to 85% renewable energies and 15% fossil fuels in the span of one generation.

In a nutshell, transforming organizations is challenging. However, companies like Ørsted are the living proofs that it is possible. The ability of companies to change and reinvent themselves is crucial for the green transition.

By Marie Goepfert and Lucrezia Manta

Sources:

www.reuters.com/article/us-energy-summit-dongenergy-strategy-idUSTRE64P68I20100526. https://about.bnef.com/blog/dong-energys-zero-subsidy-offshore-wind-farms-ripe-farm-downs/. eacd-online.eu/from-90-fossil-fuels-to-90-renewables-the-orsted-transformation-story/ www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/orsteds-renewable-energy-transformation orsted.com/en/insights/white-papers/green-transformation-lessons-learned hbr.org/2019/09/the-top-20-business-transformations-of-the-last-decade https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisabodell/2022/03/28/most-change-initiatives-fail—heres-how-toeat-the-odds/?sh=4e56896d22ee https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/changing-change-management www.corporateknights.com/clean-technology/black-green-energy/